Exclusión-inclusión: El caso del exilio político germanoparlante en México y la solidaridad antifascista de artistas mexicanos del Taller de Gráfica Popular

(pp. 140-154; DOI: 10.23692/iMex.19.10)

Loading...

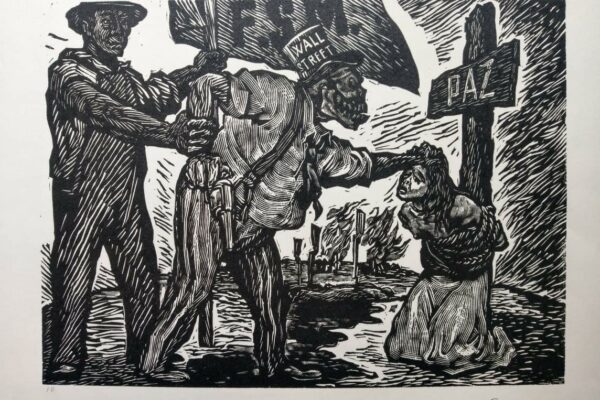

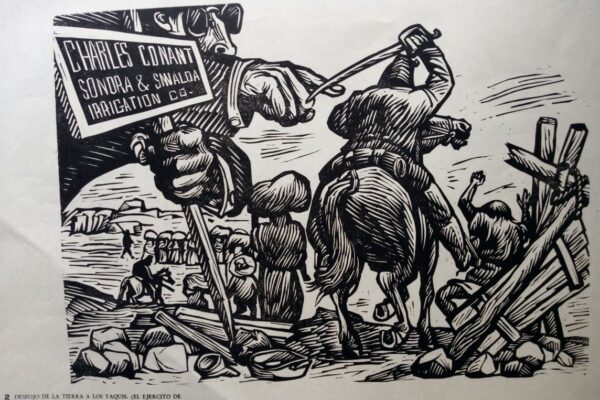

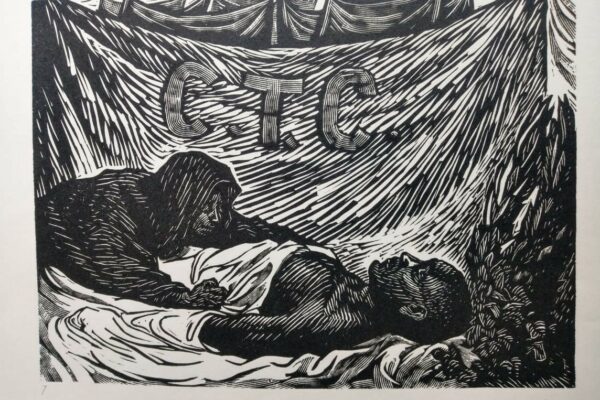

Loading...Litographies by Leopoldo Méndez, reproduced with permission of the Fondo Histórico Lombardo Toledano (archivo histórico Lombardo Toledano).

Prof. Dr. Lizette Jacinto

Since December 2015, she has been a Faculty member of the Department of History of the Institute of Social Sciences and Humanities “Alfonso Vélez Pliego” at the Benemeritus Autonomus University of Puebla (Universidad Autónoma de Puebla, BUAP) in Puebla, Mexico. She obtained her Ph.D. from the University Witten-Herdecke in Germany (advisor: Prof. Jörn Rüsen) in 2010, the Master in History degree from the Benemeritus Autonomus University of Puebla (Universidad Autónoma de Puebla, BUAP) in Puebla, Mexico, in 2004, and the Bachelor in History degree from the National Autonomous University of Mexico (Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, UNAM), in Mexico City, Mexico, in 2002. Between 2004 and 2008 she was a member of the Institute for Advanced Cultural Studies, (Kulturwissenschaftliches Institut, KWI), in Essen, Germany. From 2009 till 2014, she was respectively a lecturer at the University of Cologne, and the Heinrich-Heine University of Düsseldorf, Germany. Since 2013 she is member of the International Network for History Theory (INTH), and since 2017 a member of the National System of Researchers (SNI) in Mexico. She edited, together with Eugenia Scarzanella, the book Género y Ciencia en América Latina, published by Iberoamericana Vervuert, Germany, in 2011, and was the single editor of the book Racism, body and violence in Latin America, published by BUAP – Ediciones Del Lirio, Mexico, in 2019. She has been a guest lecturer at universities in Germany, Italy, Belgium and Mexico and has organized several international conferences and symposia.

The following article deals with the experience of leftist and German-speaking political exiles in Mexico, following the persecution of National Socialist and Fascist governments perpetrated against them in Europe in the late 1930s and 1940s. It parts from the premise that the National Socialist construction that emerged in Germany and elsewhere at that time was built on exclusion. And, who were the social groups left out of this project? Although in the first instance it was the political dissidents and critics of the regime, very early on, other groups were also pointed out as not suitable for the project of the Aryan society; for example, the Roma and the Sinti peoples, the so-called Asoziale (anti-socials), the mentally ill, the feminists and, last but not least, the Jewish people, a group dealt with the tragically famous “Final Solution”. In contrast to this exclusion, the forced political exile of the leftist intelligentsia fleeing Europe found in the local politicized left-oriented groups in Mexico a niche of inclusion. Not all of the leftist oriented organizations accepted the newcomers, of course, but there were enough organizations and associations that showed solidarity on the local, national and international levels. But not all the exiles had the same experience. The latter is evident if two separate cases are examined: those of Anna Seghers and Alice Rühle-Gerstel, respectively. The first one was an orthodox communist who enjoyed recognition and acceptance in the leftist academic circles of that time, and still does, whilst the second one, a feminist, a socialist-humanist, was rejected by the leftist preponderant groups, was isolated, and finally fell into oblivion. Dissidence and estrangement, occurring on a daily basis, formed part of both their experiences that turned out being completely opposite despite the many similarities they shared, revealing important dissimilarities within the group of leftist German-speaking exiles. Finally, the article addresses the solidarity shown towards the exiles by the group of artists and printmakers that formed the Taller de Gráfica Popular (Popular Graphics Workshop) in Mexico at that time, and by one of the most emblematic printmakers, Leopoldo Méndez, who provided poster designs to disseminate the exile group’s propaganda that focused on spreading the ideas if their anti-fascist struggle. As an example of this, El libro Negro (The black book), a book denouncing fascist practices world-wide, although organized and published in Mexico, enjoyed international support of anti-fascist intellectuals.

El siguiente artículo aborda la experiencia del exilio político de izquierda y germanoparlante en México y a raíz de la persecución de los gobiernos nacionalsocialista y fascistas en Europa a finales de la década de los treinta y de los cuarenta. En ese sentido, partimos de la premisa que la construcción nacionalsocialista en Alemania se fundamentó sobre la base de la exclusión, ¿quiénes quedaron fuera de este proyecto?, si bien en primera instancia fueron los disidentes políticos y críticos al régimen, muy tempranamente, también señalaron otros grupos como no aptos para el proyecto de la sociedad aria, por ejemplo, los pueblos Roma y Sinti, los denominados asociales, los enfermos mentales, las feministas y, por último pero no menos importante, el pueblo judío y con las consecuencias de la elaboración de la denominada “Solución Final”. En contraposición, el exilio político de izquierda en México halló en los grupos politizados de ideología de izquierda un nicho de inclusión, por supuesto no todos, pero sí hubo organizaciones y asociaciones que se solidarizaron desde el ámbito local, nacional hasta el internacional. Lo anterior quedará de manifiesto en dos casos: Anna Seghers y Alice Rühle-Gerstel, la primera, una comunista ortodoxa que hasta la fecha goza de reconocimiento, la segunda, una feminista, socialista-humanista, que cayó en el olvido. Mambos casos representan la disidencia y distanciamiento que también se dio, cotidianamente, en el ámbito de los grupos de exiliados en México. Por último, se aborda la solidaridad mostrada por el grupo de artistas y grabadores, por ejemplo, El Taller de Gráfica Popular y uno de los grabadores más emblemáticos, Leopoldo Méndez, quien proporcionó diseños de cárteles para difusión de la propaganda del grupo de exiliados y su lucha antifascista, por ejemplo en el El libro Negro, un libro de denuncias de las prácticas fascistas y organizado desde México pero, que contó con el apoyo internacional de intelectuales antifascistas.

Articles

Vittoria Borsò – Repensar la globalizacion desde la literatura mexicana

Gesine Müller – Paz entre literatura mundial y literaturas del mundo

Anne Kraume – Altamirano y los trenes

Sara Poot Herrera – Arreola y su estética del zigzag

Hermann Herrlinghaus – La búsqueda de otra dimensión de la realidad

José Ramón Ruisánchez Serra – Apercepción en Amado Nervo

Edith Negrín – Traven: primer encuentro con los indios mexicanos

Roger Friedlein – Estrategias de personalización en literaturas nacionales

Lizette Jacinto – Exilio político germanoparlante

Jacobo Sefamí – De ida y vuelta: Myriam Moscona

Stephanie Schütze – Guadalupe Tonantzin: una santa transcultural

Tanius Karam Cárdenas – Entre muros y túneles: necropolítica en México

Sandra L. López Varela – Etnoarqueología para el combate a la pobreza

Sandra del Pilar – El sueño incobrable de la transparencia absoluta